A Snapshot of Occupational Licensing in Oregon

September 14, 2023

Kentucky General Assembly – Special Committee Certificate of Need Task Force

September 19, 2023Assessing Scope of Practice for Marriage/Family Therapists and Clinical Social Workers in the US

Michael Thom1 and Conor Norris2

1: University of Southern California

2: Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation at West Virginia University

In 2022, over 40 million adults in the United States reported consistent anxiety symptoms, and some 15 million experienced depression.[1] Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate 50,000 suicide deaths occurred the same year, with a sharp increase among those 45 and older.[2] In addition to their incalculable emotional toll, mental health challenges have economic consequences: one recent estimate places the annual cost above $300 billion.[3]

Minimizing the emotional and financial burdens of those struggling with mental health challenges requires timely diagnosis and treatment, but individuals needing care face obstacles to both. Cost is one factor. According to the White House Council of Economic Advisers, an inability to afford mental health care is the primary reason individuals do not seek it.[4] Lack of access is another barrier. The American Association of Medical Colleges notes that in 2021 “less than one-third of the U.S. population (28%) lives in an area where there are enough psychiatrists and other mental health professionals available to meet the needs of the population.”[5] Long wait times for professional help can allow a patient’s mental health to worsen and place their lives at risk.

Occupational licensing regulations contribute to the lack of access which, in turn, increases mental health treatment costs and delays treatment. State governments mandate that most mental health professionals earn a post-graduate degree, pass one or more exams, complete thousands of hours of supervised practice, and pay hundreds if not thousands of dollars in fees before granting a license. Research consistently finds evidence that occupational licensing laws reduce the supply of professionals, by as much as 27 percent.[6]

In addition to controlling who can enter the profession, states also impose limits on practice, determining what treatments mental health professionals can provide. In practice, these laws also restrict the supply of professionals able to offer the services. Research finds evidence that expanding scope of practice for mid-level healthcare professionals increases access to services and decreases costs.[7]

This policy brief discusses variations in those limits, known as scope of practice rules, for two mental health professions: licensed marriage and family therapists (LMFTs), who tend to focus on family and interpersonal conflicts, and licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs), who often focus on individual mental health issues. Although their specialties differ, both professionals are well-positioned to diagnose and treat the most common mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression. Before licensing either professional, every state government requires at least a master’s degree in a related field in addition to supervised practice. Increasing access to their services is vital to reversing recent increases in the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and suicide. To increase access to mental health treatment, states should:

- Harmonize scope of practice, remove unnecessary terms, and define unclear terms and

- Expand scope of practice to allow LMFTs and LCSWs to diagnose and treat basic anxiety and depression.

A CLOSER LOOK AT SCOPE OF PRACTICE LANGUAGE FOR LMFTs AND LCSWs

Occupational licensing is designed to protect consumers by setting minimum standards to enter a profession. However, licensing regulations go beyond stipulating required education, training, and testing requirements. State legislatures, licensing agencies, or both also restrict the services a professional can legally provide after they obtain a license. These restrictions are known as “scope of practice” rules. Services provided within a profession’s scope of practice are considered legal and permissible, but not mandatory. Services outside the scope are considered illegal and may trigger consequences, including fines, license suspension, or license revocation.

Because occupational licensing laws are passed at the state level independently, inconsistencies arise between states. Every state government has a separate scope of practice for LMFTs and LCSWs. Nevertheless, there are some consistencies across the states. Interestingly, none of the states’ language for either occupation includes “depression,” “anxiety,” or “suicide.” And for marriage and family therapists, just seven states reference “divorce.”

When it comes to diagnosing and treating common mental health conditions, scope of practice language for LCSWs is relatively consistent. Based on our review of scope of practice language, available from each state’s appropriate board for licensing therapists and/or social workers, 47 states clearly allow LCSWs to diagnose and treat anxiety, depression, and at least some other conditions. The scope of practice language in other states isn’t as clear:

- Delaware permits LCSWs to provide counseling, but it does not permit them to administer psychological tests—tests that may be necessary to diagnose the mental health condition for which a person seeks counseling.

- Indiana lets LCSWs use “psychosocial evaluations” and “appraisal instruments,” but the state’s scope of practice language indicates their use cannot “include diagnosis.”

- Montana allows LCSWs to administer a mental health test “if the licensee is qualified to administer the test and make the evaluation and assessment.” But the scope of practice does not include clarity on what how to determine if an LCSW is sufficiently qualified.

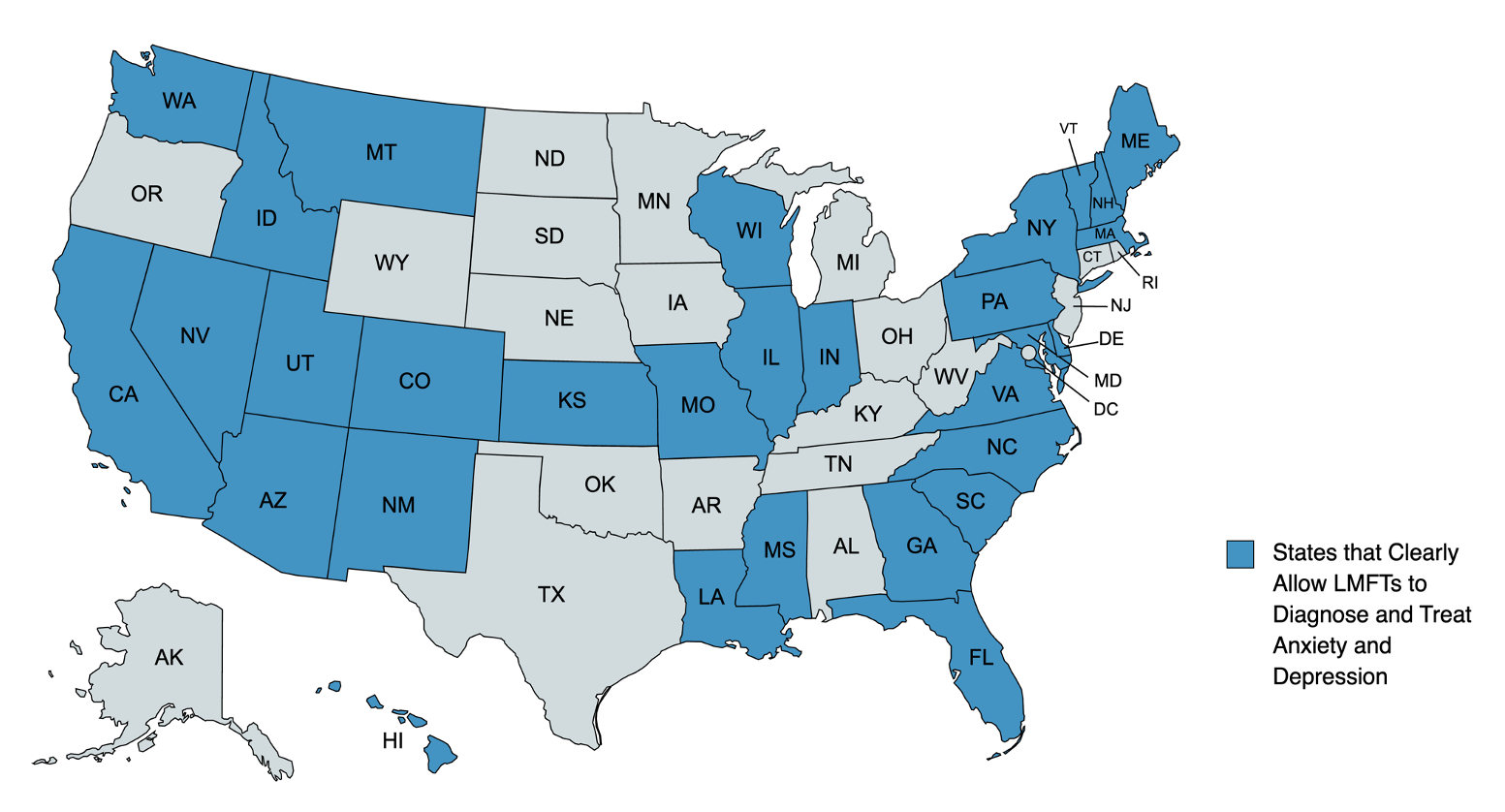

LMFTs’ scope of practice is less consistent than for LCSWs. In thirty states, illustrated in the map below, the language clearly permits LMFTs to diagnose and treat conditions like anxiety and depression. But one state, Kentucky, appears to prohibit it. That state’s language limits LMFTs to identifying and treating “conditions related to marital and family dysfunctions” and, like Delaware’s restriction on LCSWs, Kentucky prohibits LMFTs from “administer(ing) or interpret(ing) psychological tests.”

The remaining states’ scope of practice is either unclear or ambiguous regarding LMFTs’ permissible services. Ohio’s language says, in part, that independent marriage and family therapists—that state’s name for an LMFT—“may diagnose and treat mental and emotional disorders.” Yet it also says marriage and family therapists “may not diagnose, treat, or advise on conditions outside the recognized boundaries of the independent marriage and family therapist’s competency.” The scope of practice does not explain or provide guidance on how to determine those boundaries or competencies.

|

Figure 1: States that Clearly Allow LMFTs to Diagnose and Treat Anxiety and Depression

|

|

| Notes: Current as of August 2023. Source: Individual state administrative rules or statutory language on LMFT scope of practice. |

In Rhode Island, LMFTs can “engage in psychotherapy of a nonmedical and nonpsychotic nature” but the state doesn’t explicitly say that they can diagnose mental health conditions. However, for a different occupation—clinical mental health counselor—Rhode Island’s scope of practice differentiates psychotherapy from diagnosis. Thus, if the state considers psychotherapy and diagnosis as separate activities, then Rhode Island’s scope of practice apparently allows LMFTs to provide therapy for mental health conditions, but not diagnose them.

Tennessee’s scope of practice is similarly confusing. It says LMFTs can engage in the “diagnosis and treatment of cognitive, affective and behavioral problems and dysfunctions within the context of marital and family systems.” But LMFTs cannot “perform psychological testing intended to measure and/or diagnose mental illness.” Yet the state permits LMFTs to “administer and utilize appropriate assessment instruments that measure and/or diagnose, cognitive, affective and behavioral problems and dysfunctions of individuals in the context of marital and family systems.” Therefore, LMFTs in Tennessee cannot perform psychological testing, but can use “assessment instruments” for issues limited to “the context of martial and family systems.”

Several other states impose a similar restriction on LMFTS—i.e., that their services must only address issues “within the context of marriage”—or “marital”—“and family systems.” For example, Oklahoma permits LMFTs to assess, diagnose, and treat “cognitive, affective, or behavioral” conditions only “within the context of marital and family systems.” It does not define what that phrase means, nor do the other states with similar provisions: Nebraska, South Dakota, Texas, West Virginia, and Wyoming.[8]

Overall, states impose more scope of practice restrictions on LMFTs than LCSWs, and some of the language that pertains to LMFTs begs for clarification. Still, the restrictions may not be necessary, given the requirements to become an LMFT or LCSW. Under current regulations, a professional in either field must possess a master’s degree from an accredited university that follows a state-prescribe curriculum, pass one or more licensing exams, and complete additional supervised practice. Many states view that as sufficiently qualified to diagnose anxiety and depression. But many do not, making it harder for residents to obtain timely mental health treatment.

RECOMMENDATIONS

This brief’s review of scope of practice language for LCSWs and LMFTs suggests that state policymakers should consider two reforms.

First, states with ambiguous or restrictive scope of practice language for LMFTs should clarify and expand it to include diagnosis and treatment of anxiety and depression. Some states should also consider removing the restriction that LMFTs only operate within the context of a marital or family relationship. Most state governments do not include this type of language, and in those that do, the concept is ill-defined, making it of little use to professionals or consumers.

Second, states should harmonize LCSW and LMFT scope of practice language regarding anxiety and depression diagnosis and treatment. Licensing requirements for each occupation are comparable—both require a master’s degree, for example, and passing a national exam—which should be sufficient preparation to treat basic mental health issues.

Both LCSWs and LMFTs have the necessary skills and training to treat common mental health issues like anxiety and depression. Given the difficulties that patients face with both cost and access for mental health treatment, these professions provide a valuable resource. States should implement reforms to make it easier for LCSWs and LMFTs to provide treatment for common mental health conditions.

[1] Schiller, Jeannine S., and Tina Norris. 2023. “Early Release of Selected Estimates Based on Data From the 2022 National Health Interview Survey.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease202304.pdf.

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. “Suicide Data and Statistics.” Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html.

[3] Greenberg, Paul E., et al. 2021. “The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018).” Pharmacoeconomics 39(6): 653-665.

[4] The White House Council of Economic Advisors. 2022. “Reducing the Economic Burden of Unmet Mental Health Needs.” Issue Brief. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2022/05/31/reducing-the-economic-burden-of-unmet-mental-health-needs/.

[5] Modi, Hemangi, Kendal Orgera, and Atul Grover. 2022. “Exploring Barriers to Mental Health Care in the U.S.” Issue Brief. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/advocacy-policy/aamc-research-and-action-institute/barriers-mental-health-care

[6] Blair, Peter Q., and Bobby W. Chung. “How much of barrier to entry is occupational licensing?.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57.4 (2019): 919-943.

[7] McMichael, B. (2018). Beyond physicians: the effect of licensing and liability laws on the supply of nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 15(4), 732-771.; Timmons EJ, Norris C, Martsolf G, Poghosyan L. Estimating the Effect of the New York State Nurse Practitioners Modernization Act on Care Received by Medicaid Patients. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2021;22(3):212-220.

[8] Wyoming’s scope of practice language is the most detailed among these states, but it stops short of clearly indicating that an LMFT providing services there could diagnose or treat someone with anxiety or depression without it occurring “within the context of marriage and family systems.”